Soot from firestorms would reduce crop production for years.

The concept of nuclear winter — a years-long planetary freeze brought on by airborne soot generated by nuclear bombs — has been around for decades. But such speculations have been based largely on back-of-the-envelope calculations involving a total war between Russia and the United States. Now, a new multinational study incorporating the latest models of global climate, crop production and trade examines the possible effects of a less gargantuan but perhaps more likely exchange between two longtime nuclear-armed enemies: India and Pakistan. It suggests that even a limited war between the two would cause unprecedented planet-wide food shortages and probable starvation lasting more than a decade. The study appears this week in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Of an estimated 14,000 nuclear warheads worldwide, close to 95 percent belong to the United States and Russia. India and Pakistan are thought to have about 150 each. The study examines the potential effects if they were to each set off 50 Hiroshima-size bombs — less than 1 percent of the estimated world arsenal.

In addition to direct death and destruction, the authors say that firestorms following the bombings would launch some 5 million tons of soot toward the stratosphere. There, it would spread globally and remain, absorbing sunlight and lowering global mean temperatures by about 1.8 degrees C (3.25 F) for at least five years. The scientists project that this would in turn cause production of the world’s four main cereal crops — maize, wheat, soybeans and rice — to plummet an average 11 percent over that period, with tapering effects lasting another five to 10 years.

“Even this regional, limited war would have devastating indirect implications worldwide,” said Jonas Jägermeyr, a postdoctoral scientist at the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies who led the study. “It would exceed the largest famine in documented history.”

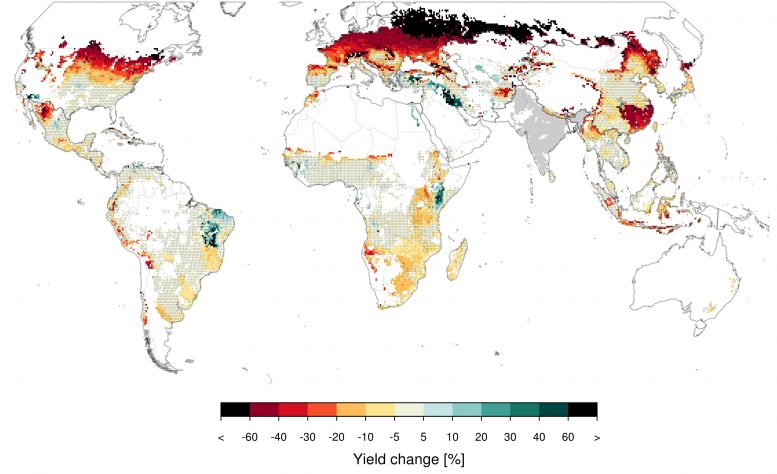

According to the study, crops would be hardest hit in the northerly breadbasket regions of the United States, Canada, Europe, Russia and China. But paradoxically, southerly regions would suffer much more hunger. That is because many developed nations in the north produce huge surpluses, which are largely exported to nations in the Global South that are barely able to feed themselves. If these surpluses were to dry up, the effects would ripple out through the global trade system. The authors estimate that some 70 largely poor countries with a cumulative population of 1.3 billion people would then see food supplies drop more than 20 percent.

Some adverse effects on crops would come from shifts in precipitation and solar radiation, but the great majority would stem from drops in temperature, according to the study. Crops would suffer most in countries north of 30 degrees simply because temperatures there are lower and growing seasons shorter to begin with. Even modest declines in growing-season warmth could leave crops struggling to mature, and susceptible to deadly cold snaps. As a result, harvests of maize, the world’s main cereal crop, could drop by nearly 20 percent in the United States, and an astonishing 50 percent in Russia. Wheat and soybeans, the second and third most important cereals, would also see steep declines. In southerly latitudes, rice might not suffer as badly, and cooler temperatures might even increase maize harvests in parts of South America and Africa. But this would do little to offset the much larger declines in other regions, according to the study.

Since many developed countries produce surpluses for export, their excess production and reserves might tide them over for at least a few years before shortages set in. But this would come at the expense of countries in the Global South. Developed nations almost certainly would impose export bans in order to protect their own populations, and by year four or five, many nations that today already struggle with malnutrition would see catastrophic drops in food availability. Among those the authors list as the hardest hit: Somalia, Niger, Rwanda, Honduras, Syria, Yemen, and Bangladesh.

If nuclear weapons continue to exist, “they can be used with tragic consequences for the world,” said study co-author Alan Robock, a climatologist at Rutgers University who has long studied the potential effects of nuclear war. “As horrible as the direct effects of nuclear weapons would be, more people could die outside the target areas due to famine.”

Previously, Jägermeyr has studied the potential effects of global warming on agriculture, which most scientists agree will suffer badly. But, he said, a sudden nuclear-caused cooling would hit food systems far worse. And, looking backward, the effects on food availability would be four times worse than any previously recorded global agriculture upsets caused by droughts, floods, or volcanic eruptions, he said.

The study might be erring on the conservative side. For one, India and Pakistan may well have bombs far bigger than the ones the scientists use in their assumptions. For another, the study leaves India and Pakistan themselves out of the crop analyses, in order to avoid mixing up the direct effects of a war with the indirect ones. That aside, Jägermeyr said that one could reasonably assume that food production in the remnants of the two countries would drop essentially to zero. The scientists also did not factor in the possible effects of radioactive fallout, nor the probability that floating soot would cause the stratosphere to heat up at the same time the surface was cooling. This would, in turn, cause stratospheric ozone to dissipate, and similar to the effects of now-banned refrigerants, this would admit more ultraviolet rays to the earth’s surface, damaging humans and agriculture even more.

Much attention has been focused recently on North Korea’s nuclear program, and the potential for Iran or other countries to start up their own arsenals. But many experts have long regarded Pakistan and India as the most dangerous players, because of their history of near-continuous conflict over territory and other issues. India tested its first nuclear weapon in 1974, and when Pakistan followed in 1998, the stakes grew. The two countries have already had four full-scale conventional wars, in 1947, 1965, 1971 and 1999, along with many substantial skirmishes in between. Recently, tensions over the disputed region of Kashmir have flared again.

“We’re not saying a nuclear conflict is around the corner. But it is important to understand what could happen,” said Jägermeyr.

Reference: “A regional nuclear conflict would compromise global food security” by Jonas Jägermeyr, Alan Robock, Joshua Elliott, Christoph Müller, Lili Xia, Nikolay Khabarov, Christian Folberth, Erwin Schmid, Wenfeng Liu, Florian Zabel, Sam S. Rabin, Michael J. Puma, Alison Heslin, James Franke, Ian Foster, Senthold Asseng, Charles G. Bardeen, Owen B. Toon and Cynthia Rosenzweig, 16 March 2020, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1919049117

The paper was coauthored by a total of 19 scientists from five countries, including three others from Goddard, which is affiliated with Columbia University’s Earth Institute: Michael Puma, Alison Heslin and Cynthia Rosenzweig. Jägermeyr also has affiliations with the University of Chicago and Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research.

1 Comment

i’m old and lived through the first cold war. i never really believed that the US and the USSR would deliberately start a nuclear war because they were both governments that claimed to represent and answer to the people of their countries and would not willingly kill a huge proportion of those people.

india and pakistan are democratic theocracies with governments that answer to gods, not the people. i am not in the least bit confident they put the people over their religion.